- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to secondary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Richard III – A Heritage of Hilarity: Scott Blogs On The History of R3!

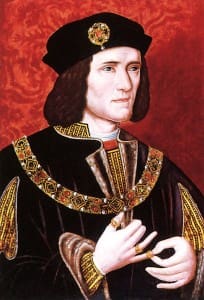

Richard III is, without question, one of Shakespeare’s most compelling inventions. As an historical figure, Richard is among the most relevant and important monarchs in England’s history, and as a dramatic character, Richard is among the Bard’s most delicious and well-crafted villains. But, as with almost all of Shakespeare’s works, he didn’t invent the character, the text, the plot or the language on his own; in fact, a number of important histories, plays and narratives are at the heart of Shakespeare’s Richard III.

Richard III is, without question, one of Shakespeare’s most compelling inventions. As an historical figure, Richard is among the most relevant and important monarchs in England’s history, and as a dramatic character, Richard is among the Bard’s most delicious and well-crafted villains. But, as with almost all of Shakespeare’s works, he didn’t invent the character, the text, the plot or the language on his own; in fact, a number of important histories, plays and narratives are at the heart of Shakespeare’s Richard III.

Among the most powerful literary influences on Shakespeare were the standard texts that he turned to time and again for story ideas; Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland which is the primary source for Richard III’s plot and history. But in order to understand more about Richard as a dramatic character, Shakespeare turned to Edward Hall’s The Union of The Two Noble and Illustrious Families of Lancastre and Yorke from 1550 which, itself, was a version of Sir Thomas More’s The History of King Richard The Thirde from 1513. Scholars note that, prior to Shakespeare’s staging of Richard III in 1592 or 1593, there were a number of quite popular and successful dramatizations of King Richard’s story, including The True Tragedy of Richard III, an anonymous play, and Richardus Tertius, a Latin drama by Dr. Tomas Legge performed in 1597. It is interesting to note that one of Shakespeare’s most famous lines, “A horse, a horse! My kingdom for a horse!” was taken (but improved upon) from the anonymous play where Richard cries “A horse, a horse, a fresh horse!”

It is from the three historical texts, primarily, that Shakespeare got the content for his play. From Holinshed comes the historical and political content (the plot) and, from Sir Thomas More comes the depiction of Richard as a brilliantly twisted villain.

But all of these texts, and Shakespeare’s own representation of Richard, owe much more to a far earlier social influence: The Catholic Church.

Hundreds of year before Shakespeare, the Church employed a remarkable dramatic instrument to teach moral lessons to their parishioners; staged productions filled with Catholic doctrine and Christian values called Morality Plays. For the most part, these scripted performances were focused on temptation, on repentance and salvation, and on God’s divine plan for humankind. These Morality Plays (the earliest known is The Castle of Perseverance although the most well-known is Everyman) were thought to have been written by clergymen as an extension of their sermons or as entertainments at the end of services, and often (almost always) included characters that were…shall we say…fairly easy to comprehend.

Hundreds of year before Shakespeare, the Church employed a remarkable dramatic instrument to teach moral lessons to their parishioners; staged productions filled with Catholic doctrine and Christian values called Morality Plays. For the most part, these scripted performances were focused on temptation, on repentance and salvation, and on God’s divine plan for humankind. These Morality Plays (the earliest known is The Castle of Perseverance although the most well-known is Everyman) were thought to have been written by clergymen as an extension of their sermons or as entertainments at the end of services, and often (almost always) included characters that were…shall we say…fairly easy to comprehend.

Their names? Idleness, Envy, Sloth, Shame, Death, Knowledge, Beauty, Strength, Good Deeds and…of course…Vice.

The plots were equally simplistic, and often comic. The hero, (sometimes called Everyman or Man), is tempted by a character (with a name like Sin) and, ultimately, through the teachings of the Church, either denies temptation or is redeemed from temptation. Pretty straight forward, right?

In fact, it may have been too straight forward. Kaitlin Steiner, in her essay From Classic Morality Play Tradition to Macbeth, writes, “Due to the fact that many of the early Moralities were written by clergymen strictly to stress spiritual righteousness and strongly discourage sinful behavior, in many cases the author is unknown, the quality of writing is uneven, characterization is also crude and naïve, and there is little attempt to portray psychological depth.” Sounds delightful.

Which is why, according to Steiner and others, Morality Plays began to change, deepen and grow in complexity during the early onset of the Renaissance. Steiner writes, “The plays became a lot less sermon-like, the characters moving from allegorical in nature to actual characters with human names and attributes. They ceased to be metaphors. The plays became less about eternal after-life salvation and more about being brought to earthly justice.”

Joan George, in her 1968 work The Evolution the Vice Character From The Morality Plays To Renaissance Drama, writes, “the playwrights were beginning to put evil where it really exists—in the mind of man. By the time of the Tudor Interludes, the Vice character was becoming a man with an evil nature, and his old allegorical name and nature were being concealed.”

These new visions of Morality Plays were also meant to be very, very funny. George writes, “The Vice character would provide the comic relief for the play…often through mocking and ridicule…and, in the case of the villain-Vice, is malicious in nature and inherently evil – a designing monster whose outstanding characteristics lie in his ability to plot evil by means of deceit.”

Throughout this late Renaissance period of Morality Plays, one thing did remain mostly consistent: the characters in the plays included characters who were in some way personifications of their moral qualities and the style was generally comedic. For example, in The Miraculous Apple Tree, the characters of Staunch Goodfellow and Steadfast Faith are rewarded by God for…well, for being a good fellow and for having steadfast faith…with an apple tree that is always laden with fruit; whomever touches the tree who is NOT…well…a good fellow nor had steadfast faith…is immediately stuck to the tree, leading to somewhat predictable but nevertheless comedic consequences.

The quality of the Morality Plays were often described as being carnival-like, as farcical in nature. They were often accompanied by fetes and festivals, by communal gatherings and celebrations, and by frivolity and puppet shows. They were a grand old time for the devout and, even if they were a form of indoctrination, they tried to be rollicking good fun.

Tina Blue, in her The Morality Play in English Drama writes, “Morality plays were originally quite serious in tone and style, due to their roots in religious drama. As time wore on and the plays became more secularized, they began to incorporate elements from popular farce. This process was encouraged by the representation of the Devil and his servants as mischievous trouble-makers. The Vice soon became a figure of amusement rather than moral edification. In addition, the Church noticed that the actors would often improvise humorous segments and scenes to increase the play’s hilarity to the crowd.”

Tina Blue, in her The Morality Play in English Drama writes, “Morality plays were originally quite serious in tone and style, due to their roots in religious drama. As time wore on and the plays became more secularized, they began to incorporate elements from popular farce. This process was encouraged by the representation of the Devil and his servants as mischievous trouble-makers. The Vice soon became a figure of amusement rather than moral edification. In addition, the Church noticed that the actors would often improvise humorous segments and scenes to increase the play’s hilarity to the crowd.”

So common, and so powerful, was the character of The Vice that scholars throughout the early Renaissance researched, codified and detailed the essential nature of the character. Peter Happ, in his dissertation The Vice in 1966, lists the sixty characteristics of The Vice, and they include the use of an alias, strange physical appearance, the use of asides and direct address, directly discussing his plans with the audience, disguise, long avoidance of but ultimate suffering of punishment, moral commentary, self-explanation in soliloquies, satire, attacks on women, depravity, boasting and conceit, immoral sexuality, strong logic, use of oaths and proverbs, and the seeking and enjoyment of great power.

Does that sound like anyone to you?

So much of Shakespeare’s Richard III is owed to these conceptions of the Morality Plays; the style of direct address, the way King Richard introduces himself, the physical and verbal style of the character of the King. In fact, dozens (if not hundreds) of scholarly articles and studies point to the character of the Vice as the template for Shakespeare’s Richard that it feels almost like Theatre 101 to use The Vice as a template for our Richard.

So much of Shakespeare’s Richard III is owed to these conceptions of the Morality Plays; the style of direct address, the way King Richard introduces himself, the physical and verbal style of the character of the King. In fact, dozens (if not hundreds) of scholarly articles and studies point to the character of the Vice as the template for Shakespeare’s Richard that it feels almost like Theatre 101 to use The Vice as a template for our Richard.

King Richard III: Proto-Renaissance Vice, “Shakespeare chooses to write a play emphasizing the monster rather than the supposed heroes who prevailed. In the earlier plays in the series Shakespeare had simply shown us the rise and fall of great men. But in Richard III he takes us inside the moral chaos inside the world of Richard. He is amoral, without regard for the moral consequences. He is clever and funny, a powerful superman surrounded by fools, weaklings and corporate climbers. The figure of Richard III suggests a stock figure from the old medieval dramas, the character of Vice in the morality plays….the actors who played the characters in the Morality Plays were masters of improvisation, of creating mock horror, comic terrors…chasing children in fanciful fear. But Richard doesn’t just chase the little children, he murders them. And, like the actors in the old Morality Plays, Richard is a lot like an actor who makes up his own part as he goes along. We see him change his behavior as he seeks to manipulate and control other people. If he were simply a clever deceiver, he would remain just an interesting character. It was Shakespeare’s genius to make the audience Richard’s accomplice; we enter into a criminal conspiracy with this ambitious climber. He has no really close friends; the only person he confides in throughout the play is us.”

The Vice of the old Morality Plays was so much more than just “evil” personified. He was, according to most scholars, the most popular and favorite character of the style. He brought intrigue and deceit, created laughter, engaged the audience’s sympathy through the creation of a conspiratorial relationship, asking the audience to be “in on the plot.” The Vice was a figure of the carnival, who fights established authority and embodied the audience’s anti-authoritarian impulses – he was a representation of the audiences secret desires, their frustrations, their ambitions.

It feels almost too easy, this idea of placing Richard on stage as a throwback to the Vice character of old…Which is why we aren’t going to do that to Richard. We are going to do it to the rest of the characters.

And, let’s be honest, none of the rest of the characters in this play (with perhaps the exception of the Princes and Richmond) are stalwart, upstanding moral characters.

Anthony Hammond, in his introduction to the Arden edition of Richard III, “It has often been remarked that all of the characters in the play are guilty. This is so…it is worth remembering that the motives for their behavior, when examined, are no more rational or moral that Richard’s.”

Clarence is guilty of the murder of the young Prince Lancaster and a coward. Buckingham is a willing participant in Richard’s schemes. Anne ultimately allows Richard to marry her, and Elizabeth is a conniving climber. Margaret is a murderer, Hastings blind and arrogant. None of them are likeable, and certainly not as likeable as Richard.

I have always been drawn to Richard as a character. I like him. Everyone does. He is the charming Machiavel, the gorgeous grotesque, the witty fascist, the smartest guy in the room, the hilarious schemer, and one of the only villainous characters in all of Shakespeare’s canon that I feel badly for when he loses in the end. I have always wanted Richard to win, and have wondered what the world of Shakespeare’s play would have been like had he found that horse he called for. Yeah, he is an unrepentant villain and a mass murderer, but he is just…so…damn…likeable!

You know who I can’t stand? Richmond. Smarmy, self-righteous, holier-than-thou, goody two shoes. Or Elizabeth, self-absorbed and snobbish. Margaret is a psychopath, and Hastings is a bully. Rivers is a suck-up, and the Princes? Well, I’d have a hard time not chopping their heads off, too, if I had to spend more than a few minutes in their privileged company.

I wonder about how Richard sees these figures, what they must look like to him. In the same way that they see Richard as the living manifestation of evil on earth, as a toad, as a bottled spider, as a twisted freak, as an accident of nature and a hideous blot on England’s royal houses…how do they look to Richard?

Imagine it this way: What if Richard were to be the audience for a reverse Morality Play? What if we were priests in the Church of Richard, and we were to create a performance that put Richard as the hero and the other characters as the vices of old? The personifications of depravity and degeneracy? You can feel Richard’s disdain for these people in almost every word of the play; he loathes them just as much as they do him. What does Richard see when he looks out into the world?

A kingdom populated with falseness, personal ambition, greed, and sloth. Corruptions of nature and vile self-serving pride. Arrogance and vanity, callous indifference and unearned influence. And, like the great Morality Plays upon which Richard III is based, I imagine Richard finds it all so very, very hilarious.

Scott Palmer

Artistic Director

Bag&Baggage Productions

Reader Interactions