- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to secondary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Submerged Rocks: Underneath Our Private Lives

B&B Does Noel Coward’s Private Lives

James Laver’s “The Women of 1926”

In greedy haste, on pleasure bent

We have no time to think or feel,

What need is there for sentiment,

Now we’ve invented sex appeal?

We’ve silken legs and scarlet lips,

We’re young and hungry, wild and free,

Our waists are round about the hips,

Our skirts are well above the knee.

We’ve boyish busts and Eton crops,

We quiver to the saxophone,

Come, dance until the music stops,

For who can bear to be alone?

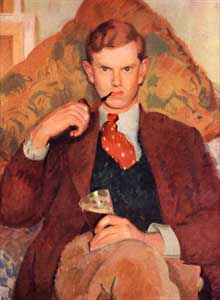

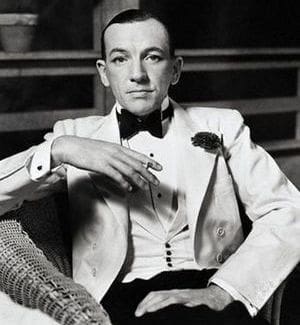

Private Lives has one of the most laudable pedigrees in the history of English drama. The play was Coward’s most successful, helping to cement his legacy and his influence…and what an influence it is; Coward has been described as the perfect entertainer. The Noel Coward society, (perhaps inclined to hyperbole when it comes to the man after whom their society is named), says, “He was simply the best all-rounder of the theatrical, literary and musical worlds of the 20th century. He invented the concept of celebrity and was the essence of chic in the Jazz Age of the 20s and 30s. His debonair looks and stylishly groomed appearance made him the icon of ‘the Bright Young Things’ that inhabited the world of The Ivy, The Savoy and The Ritz…” arts.”

Lord Louis Mountbatten said of Noël at his 70th birthday celebration in 1969: “There are probably greater painters than Noël, greater novelists than Noël, greater librettists, greater composers of music, greater singers, greater dancers, greater comedians, greater tragedians, greater stage producers, greater film directors, greater cabaret artists, greater TV stars. If there are, they are fourteen different people. Only one man combined all fourteen different labels – The Master.”

That Private Lives should have been the pebble that started the Coward avalanche is, I think, both ironic and completely appropriate; that this play that has been described by many to be fluff, frivolous, expressly empty and furiously meaningless would have helped establish Coward as one of the most influential artists EVER…well, it feels very, very fitting to me.

But I am not of a mind with many of my theatrical and critical colleagues about the nature of Private Lives; certainly it is entertaining, witty, swift, buoyant, effervescent and catty. It is, without question, all of those things, but for me it is also something else: it is deeply sad, inexplicably melancholy, and ultimately heart-breaking.

Even in one of the critical assessments I mentioned earlier, there is a hint of this sadness. John Lahr of the New Yorker wrote of Noel Coward’s Private Lives, “It is minimal as an art deco curve, it matches its content; a plotless play for purposeless people.”

A plotless play for purposeless people…

How sad.

Archie J. Loss argues that there is no future for the two leads: “they are bound to repeat themselves, playing out their scene again and again with different words and different props but always with the same result.”

Of all of the critical responses to Private Lives when it was first produced, The New Statesman came closest to my own view of the play in that it discerned a sad side to the play in its story of a couple who can live neither with nor without each other: “It is not the least of Mr. Coward’s achievements that he has … disguised the grimness of his play and that his conception of love is really desolating.”

Coward was writing at a time of enormous change, politically and socially, and many of these changes were both deeply personal and broadly universal. War, the Great Depression, unstable international economies, deepening divisions between the wealthy and the poor, terrifying crackdowns on homosexuality… At the beginning of the 1930s, more than 15 million Americans–fully one-quarter of all wage-earning workers–were unemployed. The stock market crash of October 29, 1929 provided a dramatic end to an era of unprecedented, and unprecedentedly lopsided, prosperity.

For many artists of the time, the response to these influences was to laugh (ha HA!) in the face of danger…There is in many of the leading cultural figures of the time an enthusiasm for the vitality of life, a love of culture, a love of the brashness of the contemporary, and a recognition that, (at least for many prominent gay artists and those with an eye for culture), a pervasive sense of doom, bereft of humanity…Think Edward Burra, George Brassai, and Evelyn Waugh as a few examples.

And this is what I think is hidden underneath the words of Private Lives…Coward may not have known it consciously, or he may have known it and not felt able to express it in public for fear of reprisal and renunciation, but there is something underneath the turbulent, bubbling, effervescent waters of this play; something dangerous.

Noel Coward said, of his work Fallen Angels, “Rocks are infinitely more dangerous when they are submerged, and the sluggish waves of false sentiment and hypocrisy have been washing over reality far too long already in the art of this country. …”

There are dangerous submerged rocks in this play, and like all artistic expressions throughout history, they are reflective of the rocks submerged beneath the waters of culture, politics and economics of their times.

George Brassai, a French photographer of Transylvanian descent, was one of the most prolific and influential photographers in Paris during this period. The Florida Museum of Photographic Arts quotes Brassai in its exhibition The Secret Paris of the 1930s; Brassai says “Drawn by the beauty of evil, the magic of the lower depths, having taken pictures for my ‘voyage to the end of night’ from the outside, I wanted to know what went on inside, behind the walls, behind the façades, in the wings: bars, dives, night clubs, one-night hotels, bordellos, opium dens. I was eager to penetrate this other world, this fringe world, the secret, sinister world of mobsters, outcasts, toughs, pimps, whores, addicts, and sexual inverts.”

Brassai, as an artist, wanted to know what went on INSIDE, BEHIND the walls, behind the facades. He may as well have said, “I want to know what people are really like, deep down in their private lives…”

DJ Taylor wrote a remarkable examination of the figures and characters of England’s Jazz Age entitled Bright Young People, The Lost Generation of London’s Jazz Age. In it, Taylor looks closely as the work of Evelyn Waugh, one of the most influential and prolific writers of the period. Specifically, Taylor looks at Waugh’s 1930 novel Vile Bodies (which was used for a film in 2003 called Bright Young Things), which was written the same year as Private Lives. Taylor says, “Waugh’s account of the debauched and vapid life he and his friends had led during the previous decade….the definitive exposé of this reckless, rackety Mayfair world, its endless flights to nowhere in particular, its fractured alliances and emotional dead ends.”

The self-criticism which Waugh leveled in Vile Bodies parallels the general criticism of the Bright Young Things, for whom Coward was seen as a kind of prophet; “naïveté, callousness, insensitivity, insincerity, flippancy, a fundamental lack of seriousness and moral equilibrium that sours every relationship and endeavor they are involved in.”

Taylor summarizes this approach to life as “an addictive drug, prolonged exposure to which encourages a set of false values liable to destroy the well-being of anyone ensared by them.”

In July of 2013, Private Lives returned to London’s West End at the Gielgud Theatre in London. Philip Hoare wrote a remarkable article about the public play and its private meaning that I wish I could print verbatim as my director’s notes. In brief, though, Hoare writes, “Of all Coward’s plays, Private Lives remains the most pristine, elegant example of his art. It is deceptively simple. In that, the play has the ability to sum up the restless spirit of Coward’s era. Private Lives finds its power in the hangover of a new decade, as the 1920s tripped into an uncertain future. This chamber piece seems to exist in a vacuum, a kind of stylized limbo, lacking both consequence or context, and yet it also hints at something darker in its characters’ interior lives, and that of its creator’s – both concealing and revealing at the same time.

Like so many of Coward’s play – and like his own life – Private Lives hides more than it gives away. Private Lives marked the peak of the playwright’s career. It celebrated a new society of meritocracy, a new era of celebrity and success. Yet it was written at a time of economic depression, one which echoes our own straitened times – that sense of conflict and paradox belies the apparent sheen of Coward’s play. (These characters) are young, moneyed, and carefree. They live in a newly liberated world. Indulgence, fantasy and decadence combine to create the modern, psychologically analyzed self-image of a sleek, fashionable couple; cosmopolitan, transatlantic, suave, ironic, and somewhat metrosexual…

But does all this make them happy?

Coward asks the question, but declines to answer.

Coward’s lovers are never happy together, never happy apart. They shift and change with the fluidity of the times. They live in between two terrible wars, bookended by economic collapse, disaster, totalitarian politics, global threats. Little wonder that they live for the day. That chromium gleam has its darker side; but what happens when the champagne runs out?

For all that they are portrayed – not least by themselves – as flighty, social creatures of a cynical age, their passions are intense, heartfelt, unplumbed. When the bedroom doors close, they suffer, like the rest of us.

Or rather, they suffer more, at the hands of their creator. For all his comic brilliance, Coward may have been one of the greatest tragedians of his time – one whose dark amusements still ring as clear as a chilled Martini today. That is the playwright’s greatest achievement – to make us laugh so much we forget to cry.”

Reader Interactions