- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to secondary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Timely Tragedy: Scott’s Musings on Coriolanus

I probably never would have chosen Coriolanus as a show to direct, if it had been up to me. I’ve seen it before, and read it, and had to write an essay or two about it in grad school, but it never really got to me in the way that most other Shakespeare plays have done. Even King John, that other great overlooked noble tragedy, had more of an impact on me than Coriolanus ever did. Volumnia, maybe, was compelling enough to spark my curiosity, and her big speech at the end is a remarkable piece of verse, but everyone else just seemed so…unlikeable, arrogant, uninteresting…one note.

I probably never would have chosen Coriolanus as a show to direct, if it had been up to me. I’ve seen it before, and read it, and had to write an essay or two about it in grad school, but it never really got to me in the way that most other Shakespeare plays have done. Even King John, that other great overlooked noble tragedy, had more of an impact on me than Coriolanus ever did. Volumnia, maybe, was compelling enough to spark my curiosity, and her big speech at the end is a remarkable piece of verse, but everyone else just seemed so…unlikeable, arrogant, uninteresting…one note.

And I’m not really the only one who found Coriolanus to be a bit drab. In fact, probably 85% of the greater Shakespearean world just isn’t that impressed with Shakespeare’s Roman history play.

David Wheeler in the introduction to his 1995 collection of critical essays on Coriolanus, wrote, “When discussing Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, I should begin where most writers begin: the play’s unpopularity. It is true that this, probably the last of Shakespeare’s tragedies, has, through the centuries, been one of the least acted and least known of Shakespeare’s plays.”

In fact, Coriolanus wasn’t even remotely popular when it was written, or for a period of about a century afterwards.

Written in or about 1609, Coriolanus is among Shakespeare’s later plays, although there are absolutely no recorded performances of the play during Shakespeare’s lifetime. The very first mention of any performance of the play is in adapted form, in 1682, adapted by Nahum Tate and performed at the Theatre Royal. Tate’s adaptation was called “The Ingratitude of a Commonwealth; or, The Fall of Caius Martius Coriolanus.” Critics called Tate’s adaptation “on the whole a very bad one.” Tate, it was said, “omits a good deal of the original to make room for an entirely new fifth act. His own additions are insipid, and he makes numberless unnecessary changes in the dialogue; but the first four acts of his play do not differ very materially from Shakespeare.” The focus of Tate’s adaptation was, as the new subtitle suggests, the failure of the common people to truly appreciate Coriolanus as a ruler. Their ingratitude about being starved and ruled over with an iron fist….silly poor people.

A second adaptation of Coriolanus–the work of John Dennis–was brought out at Drury Lane in November, 1719, under the title of “The invader of his country; or, The Fatal Resentment.” “Dennis,” says Genest, a critic of the period “has retained about half of the original play, which he has altered much for the worse” and again focused largely on the utter stupidity of the common people whose resentment towards the wealthy, powerful Coriolanus ultimately ended in their wholesale destruction…again, silly poor people.

A second adaptation of Coriolanus–the work of John Dennis–was brought out at Drury Lane in November, 1719, under the title of “The invader of his country; or, The Fatal Resentment.” “Dennis,” says Genest, a critic of the period “has retained about half of the original play, which he has altered much for the worse” and again focused largely on the utter stupidity of the common people whose resentment towards the wealthy, powerful Coriolanus ultimately ended in their wholesale destruction…again, silly poor people.

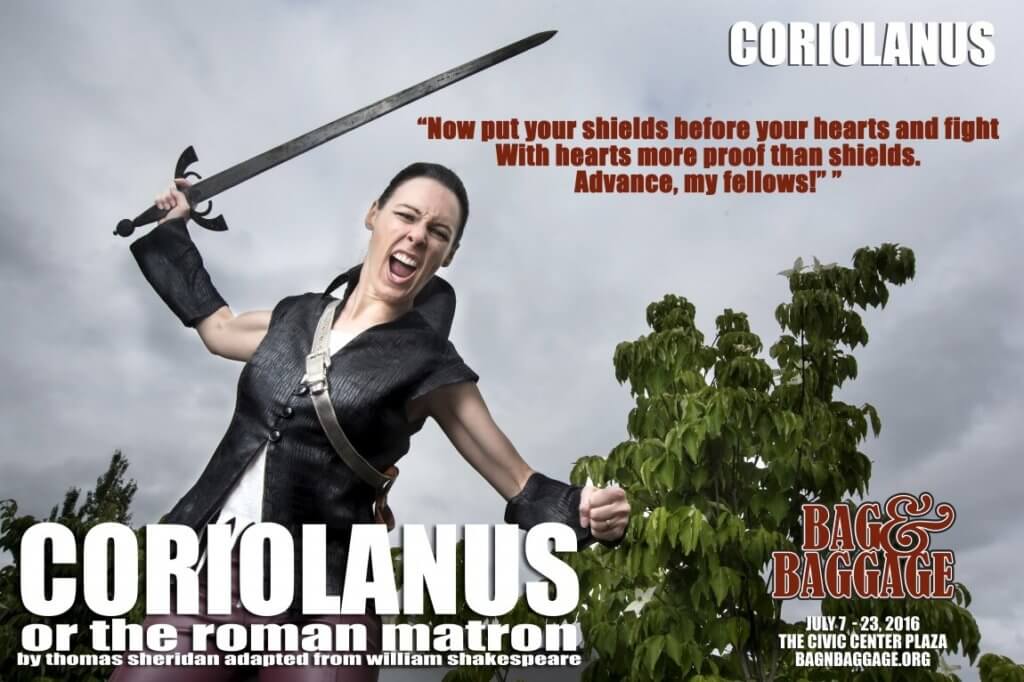

A third adaptation of Coriolanus–attributed to Thomas Sheridan, and entitled Coriolanus; or, The Roman Matron–was brought out at Covent Garden in December, 1754, and it is that adaptation that we are using as the basis for our own performance. In the Sheridan, the focus of the play shifts away from power politics to familial politics, and Sheridan explores not just the implications of the haves versus the have-nots, but also the relationship between the women in Coriolanus’ life and their influence on his choices.

Sheridan is a fascinating character, one who was often described as a “theatrical surgeon,” an Irish director, producer, and actor who was known for “grafting together” multiple plays into singular new works. Perhaps best known as an actor, Sheridan lived, according to Ester Sheldon, the only person really interested enough in Sheridan to write a biography of him, “at least three lives.” He started his career as a “gentleman actor,” when he took to the Dublin stage in January of 1743, in the title role of Richard III, although not to wide acclaim. He approached his work in the theatre with a particular attitude; the other two lives he was to live: that of a member of the landed gentry, and Irish gentleman, and also as a scholar and educator. He was thoughtful, well educated at Westminster and Trinity Colleges, and extremely well-versed in the classics, including the original source materials Shakespeare used when writing his history plays. Sheridan’s life was one of challenges – as the son of a wealthy physician from a well-respected family, Sheridan’s choice of the theatre was always in question; why would someone of such nobility lower himself to participate in the world of the theatre? Why would someone with his education and background seek fame as an actor and producer? Eventually, Sheridan would become the manager of the Smock-Alley theatre, building a name for himself and his acting troupe as one of the most successful of the period in Ireland, often in competition with important historical figures like Garrick as one of the premiere producers of theatre of the day.

Remarkably, it wasn’t until 1820, more than 200 years after it was first written, that Shakespeare’s full script actually made it to the stage- performed in London’s Drury Lane in January of that year, produced by one Mr. Elliston.

Remarkably, it wasn’t until 1820, more than 200 years after it was first written, that Shakespeare’s full script actually made it to the stage- performed in London’s Drury Lane in January of that year, produced by one Mr. Elliston.

Initially written in the early 1600s as a work of historical tragedy, Shakespeare’s Coriolanus spent its first 200 years flopping around from adaptor to adaptor, being rewritten and reimagined for a variety of political purposes. Throughout the late 1600s, Coriolanus was adapted to “illustrate the contemporary conflicts between the English monarchy and the Parilament.” David Wheeler writes, “Democratically elected officials were corrupt, incompetent, and unstable, vacillating in their views in accordance with the whims of a fickle electorate.” Better to have a leader born to it and groomed for it from birth.

Shakespearean scholar Kenneth Muir wrote, “Coriolanus is the least popular of the great tragedies due to a hero with whom modern audiences find it more difficult to sympathize than with those who commit murder or adultery. His bad qualities seem a good deal worse because we profess to believe in democracy, and the Jacobeans did not. In fact, the story of Coriolanus was nearly always told to illustrate the evils of the democractic form of government.”

Wheeler continues, “In the Restoration and throughout the 18th century, all sides used Coriolanus to advance their political positions” in essence because there is so much in the play that can be used to do so…

Is Coriolanus the bad guy? Is his arrogance and privilege ultimately the cause of his own destruction? Is it just to say that those born in power and wealth have the god given right to wield it over the uneducated, selfish masses? The plebians are not guiltless in the story, either. Their demands for food and money ignore the very real threat of an invasion from the Volsci – and Coriolanus (historically speaking), argues that keeping the grain in the Roman stores is good military planning as eventually the Roman army will need that food in order to keep the Roman state safe and secure from marauding hordes of savages. The tribunes manipulate the people back and forth, utilizing incredibly modern styles of propaganda to turn the people’s hearts away from the Roman rulers, and to dismiss the sacrifices made by the military in the interests of the people.

There are, within the story, two very distinct polarized viewpoints. As David George wrote in his edited text Coriolanus, the Critical Tradition, “This play is too complex for its own good. In order to hold all these conflicting views in balance, the reader must have a degree of detachment, unwilling to blame any of the parties at the others expense.”

David Hale writes in “Coriolanus, the Death Of A Political Metaphor,” Coriolanus is a sustained attempt to impose the analogy of the body politic on a political reality. That attempt fails. The difficulty in approaching Coriolanus has been in deciding whether the play is essentially political – perhaps a demonstration of the need for civic order – or the exhibition of the fall of a noble but deeply flawed hero. The pay is both – both public and private concerns are present throughout the play…” but in a way that is often unbalanced within individual scenes.

As with all things Shakespearean, the times determine the meaning of the plays – contemporary sensibilities shade and color the way we see and understand the plays, their characters, and their themes. Of all of Shakespeare’s plays, Coriolanus seems to be among the most liquid and mercurial in terms of the impact of the circumstances on our understanding of the play’s meanings. Unlike Hamlet or Macbeth, which are colored so carefully that there are fewer swings in interpretation, Coriolanus contains so much potential meaning that the play swings radically back and forth between warnings about tyranny and warnings about mob rule. Any reading of Shakespeare’s play could ultimately end with either interpretations…it just depends on your mood.

As with all things Shakespearean, the times determine the meaning of the plays – contemporary sensibilities shade and color the way we see and understand the plays, their characters, and their themes. Of all of Shakespeare’s plays, Coriolanus seems to be among the most liquid and mercurial in terms of the impact of the circumstances on our understanding of the play’s meanings. Unlike Hamlet or Macbeth, which are colored so carefully that there are fewer swings in interpretation, Coriolanus contains so much potential meaning that the play swings radically back and forth between warnings about tyranny and warnings about mob rule. Any reading of Shakespeare’s play could ultimately end with either interpretations…it just depends on your mood.

But, present day readings are by far less charitable towards the character of the Roman General. In essence, we have a hard time, in the 21st Century, reading anything into Coriolanus other than that he is basically an egomaniacal asshat.

William Hazlitt, one of my favorite critics of Shakespeare, writes, “The moral of Coriolanus is that those who have little, shall have less. Those who have much shall take all that others have. The people are poor, therefore they ought to be starved. They are slaves, therefore they ought to be beaten. They work hard, therefore should be treated like beasts of burden. They are ignorant, therefore they ought not to be allowed to feel that they want food, or clothing, or rest, or that they are enslaved, oppressed, and miserable.”

“The tragic struggle of the play,” says Edward Dowden, “is not that of patricians with plebeians, but of Coriolanus with his own self. It is not the Roman people who bring about his destruction; it is the patrician haughtiness and passionate self-will of Coriolanus himself…. The pride of Coriolanus is not that which comes from self-surrender to and union with some power, or person, or principle higher than oneself. It is two-fold–a passionate self-esteem which is essentially egoistic, and, secondly, a passionate prejudice of class…. His sympathies are deep, warm, and generous; but a line, hard and fast, has been drawn for him by the aristocratic tradition, and it is only within that line that he permits his sympathies to play…. For Virgilia, the gentle woman in whom his heart finds rest, Coriolanus has a manly tenderness…. In his boy he has a father’s joy…. His wife’s friend Valeria is the ‘moon of Rome.’… In his mother, Volumnia, the awful Roman matron, he rejoices with a noble enthusiasm and pride” (Shakespeare: his Mind and Art).

What was at one time viewed as a treatise on the dangers of democracy and the importance of having a noble born leader as the head of state to ensure just rule is now seen by many as an exploration of the basic evils of arrogance in our rulers, a powerful statement about the justice of democratic rule, an almost fairy tale-like morality play about what happens when a ruler ignores the needs of the ruled.

What was at one time viewed as a treatise on the dangers of democracy and the importance of having a noble born leader as the head of state to ensure just rule is now seen by many as an exploration of the basic evils of arrogance in our rulers, a powerful statement about the justice of democratic rule, an almost fairy tale-like morality play about what happens when a ruler ignores the needs of the ruled.

And who are we to reject such a reading? In fact, what better time than now to allow Shakespeare to ask us questions about what is just rule, questions about political dynasties, and about arrogance and selfish egotism in our leaders?

Scott Palmer, Artistic Director

Reader Interactions