- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to secondary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

The Shadow Of The Nightingale – Remembering Lear

There are five main sources I turned to for my adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear and they range from the ancient to the more modern. These sources both informed Shakespeare’s version of the tale and, in turn, were informed by Shakespeare’s text.

There are five main sources I turned to for my adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear and they range from the ancient to the more modern. These sources both informed Shakespeare’s version of the tale and, in turn, were informed by Shakespeare’s text.

In a way, I think I approached the adaptation of Lear with a specific outcome in mind: focus on the daughters, on their relationship with Lear, and on the textual elements of that story that survived from adaptation to adaptation that reflect that story.

When I discuss this in lectures and in classes, I often refer to “textual shadows,” elements, hints, flavors and shading of the original source materials that (no matter how radically altered or re-written) somehow remain embedded in the story.

The example I refer to regularly is the “shadow of the nightingale” in Romeo and Juliet.

During the 7th Century, an unknown Arabian poet and philosopher wrote a story called “Layla and Majnun” which told the story of two star crossed lovers who, due to a long running family feud, are refused permission to marry by their parents.

Layla’s parents force her to marry a local prince…Her husband dies, Layla mourns for the lost love of Majnun and dies of grief. Majnun is also driven mad and, although in some versions of the story he survives, in others he kills himself at the tomb of his beloved. In this story, Layla references a “nightingale” that sings to welcome the night.

This tale, originally written in the 7th century, was somewhat popular in literature throughout the Middle East until the 12th century, but it was the Persian masterpiece “Leyli and Majnun” by Nezami Ganjavi that popularized it dramatically in Persian literature. Nezami collected both secular and mystical versions of Majnun and recreated a new, more vivid picture of the famous lovers. Subsequently, many other Persian poets imitated him and wrote their own versions of the romance. Nezami “Persianised” the poem by using techniques borrowed from the Persian epic tradition, such as the portrayal of characters, the relationship between characters, description of time and setting, etc. A Latin translation of this story was known to exist in Europe throughout the 13th and 14th centuries and could very well be the original source for many of the stories that eventually influenced Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet….and, thoughout them all, the nightingale remained and ultimately found his way into Shakespeare’s tale.

Now, it may be difficult to somehow argue that a nightingale is a powerful enough symbol to have had such a defining impact on the story of the star-crossed lovers, but it is not difficult to argue that the nightingale had enough power to have been chosen, by more than 900 years’ worth of adaptors, as a key image in this particular story. There is something about the creature, something about the nature of that animal, that stayed deeply embedded in every subsequent version of the story for more than 900 years. Tough little bird…

This “shadow of the nightingale” is as close a metaphor as I can get to the elements of the Lear story that I chose to focus on in my adaptation; now, clearly, my mind was focused on my own personal history with powerful men and their daughters due to my family experience, but those elements exist in every version of the Lear story. The “shadow” of a family torn apart by madness, the unique elements of the relationship between a father and his daughters, remained throughout centuries even when Shakespeare tried (and succeeded!) to make this intimate tale the backdrop to a grand political tale of power, tyranny and narcissism. (It should not be surprising, then, that one of my favorite exchanges in the play comes when Lear asks Goneril, “Who is it that can tell me who I am?” and she replies, “Lear’s shadow.” That just gave me the shivers…)

The five texts that I plumbed for Lear’s shadow are:

- Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1577)

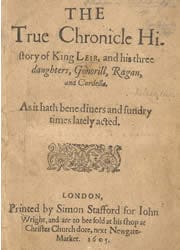

- The anonymous True Chronicle History of King Leir and His Three Daughters Gonerill, Ragan and Cordelia (1605)

- William Shakespeare’s King Lear (1608)

- Gordon Bottomley’s Lear’s Wife (1920)

- Jose Hierro’s Lear at the Cloisters translated by Gordon McNeer (1950)

(more on these later sources next time…)

I’ve already spent some time discussing the influence and nature of the first two sources, but I would say just a few more things about the anonymous Leir: Shakespeare’s reinvention of the ending is not, in my opinion, the most radical of his changes to the story. From my perspective, the most important change Shakespeare makes to Leir is that he does away with the character of Perillus in favor of a small number of new characters who divide (and, I think, dilute) the role that Perillus plays in the original. From Perillus, Shakespeare crafts Kent and the Fool, and, by doing so, crafts more complicated relationships in favor of more central, emotionally grounded ones (this may, in fact, be the most contentious of my opinions about Lear…ie…that Kent and the Fool aren’t as emotionally grounded and connected to Lear as Perillus is in the original). The other incredibly powerful element of Leir that is missing (to the detriment of the play, in my opinion) from Lear is the focus placed on the gender and role of his children…his daughters, NOT his son. Perillus acts as a “stand in” son in Leir, the son that the King wished and longed for, and the impact of that “failure to produce an heir” is seen…powerfully seen…in the character and nature of each of his daughters.

Instead, Shakespeare (as Donna Woodford writes in Understanding King Lear), “eliminate(s) this focus on the dangers of having only daughters…in part by adding the subplot of Gloucester and his sons, borrowed from Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, which clearly shows that the source of the tragedy lies in fathers misjudging their children, not in the gender of the children.”

I think it is difficult to underscore just how significant a difference this change is to the nature of the Lear story…IF the only “children” we are dealing with as characters (or as an audience, for that matter) are the daughters of an aging king, the gender of the children is crucial…no…critical…to the nature of the relationship between father and children.

If there are multiple fathers with sons and daugthers…well, it is a story about fathers and children, not fathers and daughters…

But the original source materials are ONLY about Lear and the daughters and…from my perspective…the very specific nature of the relationship between a father and his daughters hovers over the story like…well, like the shadow of a nightingale.

Scott Palmer

Artistic Director

Reader Interactions