- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to secondary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Cassie Greer Loves To Hate Mark Antony

It’s not often that I’m given the opportunity to play a historical character – or a character who is very closely based on an actual significant historical figure – and it’s so interesting how this one simple reality entirely changes my creative process. Typically, I find myself creating backstory and complications and nuances for the imaginary person whose life I am creating on stage, but here, I am given complications, nuances, contradictions, facts, and descriptions like a gift, pre-packaged with a nice little bow, ready for me to unwrap and dig into and make my own. It’s a whole different kind of workout for my imagination.

And these real-life complications and contradictions are really, really juicy.

Case in point:

This past spring, when Scott first approached me about playing Antony in this summer’s “Julius Caesar”, I got really excited and geeked out on Ancient History for a couple of weeks. After refreshing myself (junior high was a long time ago) on the First and Second Triumvirates, the Roman Senate, and the Republican Civil War, I turned more specifically to this iconic politician, decorated military man, and great orator, Mark Antony. I was ready to read all about how noble and valiant he was, and how he saved Rome from the traitors who had conspired against Caesar.

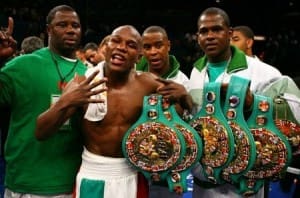

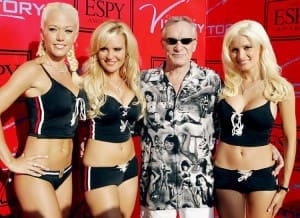

Much to my dismay, I quickly learned that Antony was actually a giant a**hole (pardon my language). Seriously though. Not just a little one. Think along the lines of Eliot Spitzer, Floyd Mayweather Jr., and Hugh Hefner, all rolled into one.

I mean, the guy ultimately chose his affair with Cleopatra over his duty to his country – not to mention his pregnant wife at home. He also:

– spent his young adult life drinking, gambling, and racking up debt

– as a general and administrator abused his power and was, again, prone to every kind of excess

– was really a much better fighter than an administrator, so when civil conflicts arose, Antony almost immediately chose violence as a solution

– was essentially responsible for starting the civil war that led to the assassination of Pompey

– his “great oratory” was of the Asiatic style, which was (according to Plutarch, who wrote the most thorough – though incredibly biased – documentation on this period of history), “suitable to his ostentatious, vaunting temper, full of empty flourishes and unsteady efforts for glory”

– he was so bad that Cicero wrote 14 (fourteen!) speeches (his “Phillippics”) condemning Antony and denouncing his conduct as a Roman

– and all his honors and his statuses removed by the Roman senate shortly after his death

To his credit, he did have (again according to Plutarch) “a very good and noble appearance; his beard was well grown, his forehead large, and his nose aquiline, giving him altogether a bold, masculine look that reminded people of the faces of Hercules in paintings and sculptures”.

Well. At least he was pretty.

Actually, it’s not all bad. Antony was really a fantastic soldier, and deserved all of the many, many recognitions he received for his valour and bravery. Plutarch also notes that “what might seem to some very insupportable – his vaunting, his raillery, his drinking in public, sitting down by the men as they were taking their food, and eating, as he stood, off the common soldiers’ tables – made him the delight and pleasure of the army.” … he was charismatic. And the life of the party. And probably always good for a good time. You would probably want to be friends with him. …you would definitely *not* want to be on his bad side…

So. Here we are. Antony the man, ripe with complexities, some of which are more than a little unsavory; and our production of “Julius Caesar”, in which Antony has to be seen as kind of the “good guy”.

Juicy complications.

Must reframe my perspectives.

Let go of previous assumptions.

This is why I do theatre.

As I grapple with this text – both Shakespeare and Cibber – I’m grateful for the simultaneous structure and challenge of these historical realities. Antony has to be sympathetic. He has to get Rome (and the audience) on his side. We have to see why some people genuinely love and respect him, despite all of the questionable choices he makes. He also has to have enough bravado and evidence of these questionable choices that we understand why all the conspirators take a mocking tone whenever they mention him… And all of Plutarch’s notes, all of Cicero’s condemnations, all of the accounts of valiant fighting and the shirking of responsibilities are what get us there. The challenge is picking up these pieces and weaving them back together in a way that is authentic – that is Antony’s but is also mine – and that serves the story we are telling here.

I am humbled. I am inspired. I am frustrated. I am curious. I hate Antony, and I love him.

And I am really, really excited for you to see this show.

Reader Interactions