- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to secondary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Not Just Nostalgia- Scott Blogs On THE GRADUATE

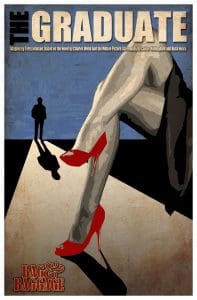

There are only a few films that can be said to truly represent a generation. The Wizard of Oz, from 1939, reflecting a world moving from gray to technicolor. The Big Chill, from 1983, calling up the angst and self-centered pain of the newly minted baby boomer generation. Star Wars, It’s A Somewhat Wonderful Life, and there are a few more. But few of them so completely and utterly embrace the nature of a generation, encapsulate a zeitgeist, as well or as with as much style as The Graduate. Nominated for seven academy awards, The Graduate was the breakthrough film for Mike Nichols, the director, and his young star, Dustin Hoffman, and has been mimicked, referenced, spoofed, satire, homaged, and honored hundreds of times since it first shook American cinema in 1967.

There are only a few films that can be said to truly represent a generation. The Wizard of Oz, from 1939, reflecting a world moving from gray to technicolor. The Big Chill, from 1983, calling up the angst and self-centered pain of the newly minted baby boomer generation. Star Wars, It’s A Somewhat Wonderful Life, and there are a few more. But few of them so completely and utterly embrace the nature of a generation, encapsulate a zeitgeist, as well or as with as much style as The Graduate. Nominated for seven academy awards, The Graduate was the breakthrough film for Mike Nichols, the director, and his young star, Dustin Hoffman, and has been mimicked, referenced, spoofed, satire, homaged, and honored hundreds of times since it first shook American cinema in 1967.

The Graduate was hailed as “the freshest, funniest, and most touching film of the year…filled with delightful surprises, cheekiness, sex, satire, irreverence toward some of the most sacred of American cows…” And there were a number of sacred cows that Americans were reconsidering during the sixties.

Benjamin Braddock was remarkably different from the other young men who were the center of most of the films created in the 1960s. He wasn’t a soldier, he wasn’t embroiled in the Vietnam War, he wasn’t a protestor or a draft dodger, and he certainly wasn’t a peacenik or a hippie. Although the war was present in the minds of all Americans, it is never directly mentioned in the film or in the novel by Charles Webb that inspired the film. Instead, Benjamin Braddock, a young, well-educated, privileged white man, is framed in all he does by his parents and his parent’s generation- a group of people still mired in the claustrophobic, insular world of the 1950s – against a backdrop of a burgeoning counter-culture that sought to not just question but dismantle the social, political, economic, and relational world of the white suburban classes.

But more than just presenting a counter-argument to the plasticized, me-first, conservative bedrock of the American middle class, The Graduate questions much more basic notions in a way that had never been seen before in popular, mainstream art: questions about sexuality and age, about intergenerational relationships, about the role of sex in marriage, about the difference between love and sex, and about empowering female sexuality.

Given that these issues are still with us today, and are still considered shocking even by contemporary standards, you can imagine just how much The Graduate rocked the boat in the late 1960s.

The film’s producer, Lawrence Truman, heard about Charles Webb’s short novel in the New York Times, picked up a copy at the airport, and decided, upon reading it, that it make an ideal film script because it was essentially written as a script. Truman bought the rights from Webb for a measly $20,000 – a pretty good amount for the time, but far short of the millions Webb might have earned had he held out for percentages, another common practice for the time. But Charles Webb was walking his talk, living his beliefs, and he was essentially a kooky artist living up to his eyeballs in an anti-establishment San Francisco. He grew up the son of a wealthy and influential San Francisco doctor, and when his parents died, he declined his massive inheritance, donated most of his personal fortune to political causes, and donated the royalties from his first novel, The Graduate, to the Anti-Defamation league. Charles Webb was not so much “successful” as an artist. Perhaps “notorious” would be a better term, and he and his partner have been described as “the world’s most notoriously eccentric arts couple.” The Turner Movie Channel writes, “Originally named Eva, she changed her name to Fred in solidarity with a California self-help group of the same name for men with low self-esteem. Their first date was in a graveyard, and they married soon after, but later divorced in protest of the lack of marriage rights for gay couples, although they are still together. Fiercely anti-materialistic, Webb was known for selling all of his material possessions, including furniture and clothing, and donating the money to various social causes. The couple gave away their tickets to the film’s premiere. They eventually settled in England, where Webb continued to write and care for his “ex-wife,” who suffered a nervous breakdown in 2001.”

The film’s producer, Lawrence Truman, heard about Charles Webb’s short novel in the New York Times, picked up a copy at the airport, and decided, upon reading it, that it make an ideal film script because it was essentially written as a script. Truman bought the rights from Webb for a measly $20,000 – a pretty good amount for the time, but far short of the millions Webb might have earned had he held out for percentages, another common practice for the time. But Charles Webb was walking his talk, living his beliefs, and he was essentially a kooky artist living up to his eyeballs in an anti-establishment San Francisco. He grew up the son of a wealthy and influential San Francisco doctor, and when his parents died, he declined his massive inheritance, donated most of his personal fortune to political causes, and donated the royalties from his first novel, The Graduate, to the Anti-Defamation league. Charles Webb was not so much “successful” as an artist. Perhaps “notorious” would be a better term, and he and his partner have been described as “the world’s most notoriously eccentric arts couple.” The Turner Movie Channel writes, “Originally named Eva, she changed her name to Fred in solidarity with a California self-help group of the same name for men with low self-esteem. Their first date was in a graveyard, and they married soon after, but later divorced in protest of the lack of marriage rights for gay couples, although they are still together. Fiercely anti-materialistic, Webb was known for selling all of his material possessions, including furniture and clothing, and donating the money to various social causes. The couple gave away their tickets to the film’s premiere. They eventually settled in England, where Webb continued to write and care for his “ex-wife,” who suffered a nervous breakdown in 2001.”

Fred and Charles had two sons, one of whom continued his parent’s artistic pursuits, gaining notoriety for cooking a copy of The Graduate and eating it with cranberry sauce.

Webb’s first novel was groundbreaking, although not particularly popular. It is one of the great frustrations of the success of the film that Webb’s writing was essentially overlooked, the nearly page-to-screen perfection of the novel passed over by the praise given to the two other writers credited with the screenplay, Buck Henry and Calder Willingham.

Henry was a friend and writer for Mel Brooks, with whom he created the spy spoof tv show Get Smart, and would later adapt the novel Catch 22 for film. Willingham was a playwright, and a respected and often controversial novelist, from Georgia. His other work for film included a number of successful partnerships with Stanley Kubrick, including Paths of Glory and an uncredited role writing scenes for Spartacus.

It was really Henry and Willingham, along with director Mike Nichols, who got the lion’s share of the praise for The Graduate, although some critics, with whom I agree, believe that the true genius of The Graduate lies with Webb who infused his novel with a flat, empty, circular, and ultimately remarkably compelling style of dialogue.

It was really Henry and Willingham, along with director Mike Nichols, who got the lion’s share of the praise for The Graduate, although some critics, with whom I agree, believe that the true genius of The Graduate lies with Webb who infused his novel with a flat, empty, circular, and ultimately remarkably compelling style of dialogue.

Andrew Sarris, a film critic from the 1970s, writes, “Charles Webb seems to be the forgotten man in all the publicity, even though 80 percent or more of the dialogue comes right out of the book. I recently listened to some knowledgeable people parcelling out writing credit to Nichols, Henry, and Willingham as if Webb had never existed, as if the quality of the film were predetermined by the quality of its script, and as if the mystique of the director counted for naught. These knowledgeable people should read the Webb novel, which reads more like a screenplay than any novel since John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.”

Lisa Rosman remarks, in her essay “Back In Bed With Mrs. Robinson,” “The Graduate only sold 5,000 copies prior to the film’s release, and is mostly comprised of dialogue with few physical descriptions and even less exposition.

In “Here’s To You, Mrs. Robinson,” Hanif Kureishi in The Guardian Book section in September of 2009, writes, “Charles Webb’s The Graduate has long been eclipsed by the film (and its soundtrack), but in its deadpan quiet stylishness it is easily its equal, being that most rare and valuable thing, a serious comic novel which both exemplifies its time and continues to speak to us.”

Nicole Smith in her 2011 Doctoral dissertation on sexuality in film, helps to give us some insight into why The Graduate spoke so powerfully to the 1960s generation, and why it might continue to be such an influential story. “A simple summary of the plot of “The Graduate” cannot possibly begin to unravel the several very complex themes that run throughout the film, especially those that relate to gender. Interestingly, gender does not stand alone as an issue and is continually addressed along with class and generational issues. The 1960s were a time when the old societal and familial values were being questioned and this film successfully addresses this dissatisfaction while at the same time relating these issues to gender, both for men and women. Under the surface, tensions resulting from issues of class and gender are always present.”

Director Mike Nichols responded brilliantly to this notion of “tensions under the surface,” to the idea that what we see on the outside is smooth, flat, and belies the roiling, boiling emotional complexity bubbling beneath. The novel and the film are often spoken of as being “deadpan,” or “deliberately impassive or expressionless.” Nichols, in fact, encouraged his cast to “take the acting out” of their work on the film and, instead, offered his commentary through groundbreaking film techniques. The design of the film helped to frame and clarify, for the audience, the reality of what was happening to these characters who did not seem, at first glance, to really be emotionally connected to their lives. It is not that they DIDN’T feel the torment of their suburban middle class existence; they did, deeply. They just didn’t show it. Instead, Nichols trapped them in scenes replete with black and white stripes reminiscent of the bars of a prison; plunged them into deep water or surrounded them by rain and storms; showed their isolation and loneliness by isolating them in a frame, and reflected their images back to them in all manner of distorted surfaces, seemingly to indicate that what we see of them as real people is the reflection and that what they truly are is distorted, tortured mirror images of themselves.

Director Mike Nichols responded brilliantly to this notion of “tensions under the surface,” to the idea that what we see on the outside is smooth, flat, and belies the roiling, boiling emotional complexity bubbling beneath. The novel and the film are often spoken of as being “deadpan,” or “deliberately impassive or expressionless.” Nichols, in fact, encouraged his cast to “take the acting out” of their work on the film and, instead, offered his commentary through groundbreaking film techniques. The design of the film helped to frame and clarify, for the audience, the reality of what was happening to these characters who did not seem, at first glance, to really be emotionally connected to their lives. It is not that they DIDN’T feel the torment of their suburban middle class existence; they did, deeply. They just didn’t show it. Instead, Nichols trapped them in scenes replete with black and white stripes reminiscent of the bars of a prison; plunged them into deep water or surrounded them by rain and storms; showed their isolation and loneliness by isolating them in a frame, and reflected their images back to them in all manner of distorted surfaces, seemingly to indicate that what we see of them as real people is the reflection and that what they truly are is distorted, tortured mirror images of themselves.

This deadpan approach, created with such genius by Webb in his circular, never ending, meaningless dialogue, was embraced by Nichols. One critic says of Dustin Hoffman that he found it difficult to make The Graduate because he was used to acting on stage. During the three week rehearsal process before filming started, Hoffman would bring all of his stage acting skills to the table and Nichols would tell him what he was doing was good but to “try it again without doing anything.” Hoffman said he soon adapted to Nichols’ minimalist style.

Hoffman’s portrayal of Benjamin was really his breakthrough role, skyrocketing him to fame, but Hoffman wasn’t Nichols’ first choice for Benjamin. Nichols considered Warren Beatty, Charles Grodin, Robert Redford, and Burt Ward (the kid who played Robin on the Batman tv show). In fact, Hoffman wasn’t even available for the role originally; he had been cast as the Nazi playwright Franz Leibkind in Mel Brooks’ The Producers and, when Hoffman bowed out of Brooks’ film, that role was recast with Kenneth Mars.

Although Benjamin is the main character, very few people really believe that the film is about him.

In “Here’s To You, Mrs. Robinson,” Hanif Kureishi writes, “There were many young, disillusioned heroes being studied in the early 60s, Meursault in Camus’s The Outsider, McMurphy in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest and (of course) Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye. Like them, Benjamin is not a revolutionary; he doesn’t want to make a new, more free or equitable society. That was to come: in the mid-60s the American scene would brighten wonderfully before it darkened again. No, Benjamin merely wants to inform those around him that he hates the world they have made; it bores him, is stupid, and he cannot find a place in it. Like Melville’s Bartleby, he would just “prefer not to”.”

In fact, Barbara Shulgasser of The San Francisco Chronicle, wrote on February 14, 1967, “Director Mike Nichols and writers Buck Henry and Calder Willingham…understood that Benjamin was not exactly a man of principle. They didn’t sign him up to protest the Vietnam War or reject his parents’ wealth because of the way American rapaciousness drains the Third World’s precious natural resources. Benjamin seems all too glad to drive the nifty Alfa Romeo his parents gave him as a graduation gift. Benjamin’s dissatisfaction is never the heart of the movie because Benjamin is little more than a cipher. We root for him only because his confusion and weakness happen to pit him against the superficiality of his wealthy background, not because there is anything intrinsically heroic or admirable about him. Benjamin, in fact, is kind of a jerk.”

In fact, Barbara Shulgasser of The San Francisco Chronicle, wrote on February 14, 1967, “Director Mike Nichols and writers Buck Henry and Calder Willingham…understood that Benjamin was not exactly a man of principle. They didn’t sign him up to protest the Vietnam War or reject his parents’ wealth because of the way American rapaciousness drains the Third World’s precious natural resources. Benjamin seems all too glad to drive the nifty Alfa Romeo his parents gave him as a graduation gift. Benjamin’s dissatisfaction is never the heart of the movie because Benjamin is little more than a cipher. We root for him only because his confusion and weakness happen to pit him against the superficiality of his wealthy background, not because there is anything intrinsically heroic or admirable about him. Benjamin, in fact, is kind of a jerk.”

Kureishi continues, “This semi-teenage rite of passage baffles Benjamin as much as it baffles his parents. We see and hear the incomprehension in his very language, which is dull and inexpressive, as if he doesn’t really inhabit the words he uses; like everything else around him, language appears to not quite belong to him and there isn’t much he can make of it. Most of his speech consists of questions, few of which are answered, or even answerable.”

Benjamin is the surface off of which the world bounces, making indentations and damaging his shiny exterior with hundreds of thousands of pebbles. Like a man who finds himself inexplicably in the middle of a snowstorm in summer, Benjamin just doesn’t understand why this is all happening to him. And if Benjamin in the impenetrable, confused victim of a sudden hailstorm, Mrs. Robinson is the deep, dark water into which those hailstones simply vanish, without a trace.

Kureishi continues, “The triumph of the book, as of the film, is Mrs Robinson. If one essential quality of a good writer is the ability to make memorable characters who appear to transcend the work they appear in, then Mrs Robinson is one of the great monstrous creations of our time. Well-off, middle-aged, alcoholic, bitter, disillusioned, perverse and yet to be rescued by feminism, her situation is far worse than Benjamin’s.She neither hates nor loves her husband, and that seems to be all there is to it. Once more numbness is preferable to unhappiness, frustration or worse, the madness of fury. This sentimental education by an older, experienced woman is, in the end, a pedagogy of disillusionment and failure.”

Kureishi continues, “The triumph of the book, as of the film, is Mrs Robinson. If one essential quality of a good writer is the ability to make memorable characters who appear to transcend the work they appear in, then Mrs Robinson is one of the great monstrous creations of our time. Well-off, middle-aged, alcoholic, bitter, disillusioned, perverse and yet to be rescued by feminism, her situation is far worse than Benjamin’s.She neither hates nor loves her husband, and that seems to be all there is to it. Once more numbness is preferable to unhappiness, frustration or worse, the madness of fury. This sentimental education by an older, experienced woman is, in the end, a pedagogy of disillusionment and failure.”

But the story, in my mind, isn’t about Mrs. Robinson, either. She is already finished, too empty to ever be filled again, a bottomlessness that no amount of booze or sex or reprisal can fill. No, ultimately, The Graduate is about Elaine. Or, really, The Graduate is the prequel to a story that eventually will be about Elaine- the set up

Nicole Smith writes, “Benjamin’s age-appropriate love interest in the film, Elaine, offers viewers two ways of considering gender… It should be remembered that by the 1960s there were many “significant changes to the lived experiences of women… Undoubtedly, marriage and motherhood remained central to the conceptualization of womanhood but there were important shifts in attitudes toward a woman’s rights to personal fulfillment” (Fink 241). This tension between traditional versus revolutionary views on gender is represented by Elaine as she both seeks to appease the status quo as set forth by her parents and suburban society while at the same time to break free and form her own understanding of herself as a woman. It is significant that she is attending college at Berkeley because during the 1960s this was the American center of many revolutionary movements that took place during the 1960s, in terms of class, gender, and race. By placing this character within such a setting, the film is making the tension between these two understandings of traditional female roles clear. The problem with Elaine’s character, however, is that she, unlike her mother, does not clearly embody the values of the 1950s nor those of the 1960s. Instead, she blends these two and is the perfect immersion of the new and the traditional.”

Nicole Smith writes, “Benjamin’s age-appropriate love interest in the film, Elaine, offers viewers two ways of considering gender… It should be remembered that by the 1960s there were many “significant changes to the lived experiences of women… Undoubtedly, marriage and motherhood remained central to the conceptualization of womanhood but there were important shifts in attitudes toward a woman’s rights to personal fulfillment” (Fink 241). This tension between traditional versus revolutionary views on gender is represented by Elaine as she both seeks to appease the status quo as set forth by her parents and suburban society while at the same time to break free and form her own understanding of herself as a woman. It is significant that she is attending college at Berkeley because during the 1960s this was the American center of many revolutionary movements that took place during the 1960s, in terms of class, gender, and race. By placing this character within such a setting, the film is making the tension between these two understandings of traditional female roles clear. The problem with Elaine’s character, however, is that she, unlike her mother, does not clearly embody the values of the 1950s nor those of the 1960s. Instead, she blends these two and is the perfect immersion of the new and the traditional.”

In a story where both main characters are unable to find meaning in anything, Elaine represents hope; the ability to choose, to pursue, to act.

This play isn’t shtick, it isn’t a comedic walk down memory lane, full of 2 dimensional Leave It To Beaver parents, one dimensional aging succubae, or a deeply flawed anti-hero who rejects the common wisdom to find inner peace and future success; it isn’t a story about redemption, or bell bottoms and ditzy flower-children; it wasn’t ever a story about schmaltz and nostalgia for a “simpler time” or even a more “revolutionary time.” It is about the chaos, terror, and fear underneath still water, and the joy that comes from seeing what we know in ourselves in others, and then chilled, as the smile fades from our lips and the laugh breathes out, in the moment that we realize what we thought we saw was really hiding something much darker underneath.

Scott Palmer

Founding Artistic Director

Director, The Graduate

Reader Interactions